(It’s a hard road to a good meal)

The cafe where I ate my most remarkable Kenyan meal cannot be found in any guidebook or on any tourist itinerary. If I had ever set foot in the Third World before or if I’d known another soul in Africa to advise me, I probably wouldn’t have gotten within miles of the place. But then I would have missed an experience of a lifetime.

I hadn’t even expected to stay overnight in Nairobi. But after being bumped off a flight out of London and missing my only-twice-a-week connection to Madagascar, I found myself alone in a strange and daunting city for four days, with no friends and the limited options afforded by my limited funds. I couldn’t afford anything like the Hilton, so the taxi driver took me to a “secure” hotel near River Road that was one-tenth the price. Later, I learned that, according to a popular “survivor’s guide” to Nairobi, I ran a 100 percent chance of being mugged if I wandered out at night in that neighborhood. Guess I was lucky.

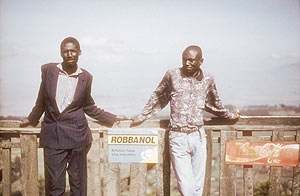

Fifteen minutes later George drove up in a dilapidated Peugeot. He introduced the driver, Bosko, whose pointed, bony frame was lost in a shiny blue suit and who spoke very little English. The guide Ben, with shaven head, sharp eyes, and a ready guffaw of a laugh, was fluent and charming.

With stops to fuel the car and change money on the black market, we bounced out of town, dodging homicidal matatu minibuses and seemingly suicidal pedestrians. We spent hours gazing down from the Rift escarpment, walking through the magically scented tea plantations, driving slowly along the rough roads, talking with villagers, and repeatedly being held up by police demanding that we pay them a cash “road tax” before allowing us to pass. It was well into the afternoon before I realized we hadn’t stopped for lunch.

“You want traditional food for lunch?” Ben asked. Sure. “You know nyama choma?” The guidebook described it as barbequed goat meat and as close as anything comes to claiming the title “national dish of Kenya.” Let’s go for it, I said. Ben says Bosko will find the very best in Kiamaiko. I had no idea where Kiamaiko was, but off we went.

The road became rougher. The houses became shacks, and the shacks became hovels. I found it difficult to believe that people could live like this. The only images I could compare it to from my experience were those of Rwandan refugee camps. But people seemed to be happily going about their business as if this was the way of the world. As indeed it was for them.

We turned the car off the dirt road and into a sea of devastation. I wouldn’t have believed one could drive into such a place, but people and goats and chickens parted before us and we inched forward past stalls and the milling hawkers selling drinks, vegetables, used clothes, anything.

I just stared and tried to take it all in. This was Kiamaiko, a slum of mammoth proportions just outside Nairobi proper. Nobody knows how many people live there, though estimates run past a million. There is no running water, there are no amenities. The only notice the government takes of Kiamaiko is to periodically bring in bulldozers and level it all. Then, within days, the shacks are rebuilt and life goes on as if nothing had happened. Ben explained this to me as we lurched along and the ruts threatened to tear the wheels off the car.

The smells were, well, rich. And when the car had taken the tenth weird turn and then lurched to a stop in a puddle, I knew I’d never find my way out alone. Bosko got out and I asked, in as calm a voice as I could manage, if this was where we were eating lunch. Ben said no. Bosko was going home to get something first. Home. HE lived here. Boy, am I glad I kept my American mouth shut.

A little while later and another few turns and puddles, we were in an area with nothing but vast herds of goats and meat hanging from the rafters of shacks. We stopped just this side of a gaggle of goats and Ben announced that we had arrived. This was where we would find nyama choma

(It’s a hard road to a good meal)

The smell was nearly overpowering. As we got out of the car and splashed over to a relatively dry spot, Ben says, “Bosko will find the best meat, We’ll go get a drink. If they see you the price will go up.” Twin ranks of wood and tin structures stood—or, rather, staggered—down either side of the irregular pathway, ruts running with animal urine and blood. Each structure sported a large concave chopping block and meat hooks. Men were hanging meat or chopping meat while negotiating heatedly with Somali herdsmen for the price of a live goat.

We picked our way down the lane. I noticed the potholes in the mud were filled with severed goat hooves. I turned to see a butcher cut the throat of a mottled white goat and had to jog to the left to avoid the blood as it streamed steaming into the gutter. “Don’t worry,” said Ben cheerily, “That’s not the one we’re eating.”

I asked how we could be sure the meat was all right. I couldn’t conceive of any quality control being exercised in this waterless chaos. Ben tried to assure me that dozens of meat inspectors roamed Kiamaiko and that not a single animal was slaughtered without an official inspection. I wasn’t convinced but I had talked myself into believing that I could probably survive eating anything Ben was willing to eat.

Ben led me through a door I’m not sure I would have identified as a door. I found myself in an actual bar. Beer bottles were stashed behind a locked iron grate. We were the only ones in the place and it was clean and inviting. Shortly after we sat down and ordered Tusker lagers the sound system coughed and began bleating some really bad country and western music. “For my benefit?” I inquired.

“Almost certainly.”

“Well, please ask them for something else!” The music mercifully changed to Kenyan pop.

While around Nairobi most people are of Kikuyu lineage, Ben is a Luo, from Lake Victoria. He told me that he thought he was a good guide because unlike most of his compatriots who were raised in either relative or absolute poverty, he grew up with money. Then he lost it all when his father sided with the losers in the political upheaval of 1978. From private school to hitting the streets at age eleven, he’d seen life from both sides. Now at twenty-eight, he spoke Kiswahili, Luo, Kikuyu, English, Spanish, “enough Japanese to make a deal,” and enough French “so that no Frenchman can speak ill of me.”

Bosko stopped in, waiting for the designated goat to be dressed out and delivered. He and Ben talked in a matter-of-fact manner about how husbands have the absolute right to beat their wives. They eyed me, waiting for an opinion. I maintained my composure while fishing for just the right response, finally saying something like, “I hope that you exercise this right rarely.” This satisfied Bosko. He smiled dismissively, claiming never to have hit his wife, in actual fact, in all their seventeen years together. Ben added seriously that he had only done so once, in order to convince her that he was not having affairs. He grinned and said it had worked and now she understood. “Now no problem,” he said. I kept my California mouth shut tight.

We sat and sipped warm lager and talked for another half an hour. Bosko finally stuck his head in and announced that the nyama choma was almost ready. Quite hungry by now, we emerged from the bar and ducked in past one of the innumerable white-hot barbecues into one of the almost-shacks. Ben proudly informed me that this was the very place the former American ambassador had patronized.

Inside stood a dozen wooden tables and a bunch of chairs, all hand-made, all surprisingly clean. There being no water for washing up, the tables were sanded down between patrons. I was amazed at how few flies there were. Ben and I sat while Bosko popped in and out at intervals to assure me the meat was coming. Finally, Bosko delivered the first plate with a broad smile and a flourish. It was plain goat meat—apparently unmarinated, unsauced, unspiced—simply cut up small with the kidneys, accompanied by another plate containing sliced tomato, red onion, cilantro, and whole long, skinny green chili peppers of a variety strange to me.

Before he allowed me to start eating Ben insisted we step out front first to wash up. Where, I wondered in horror, did the water come from? But next to the barbecue grate was a large copper kettle perched over a low fire. From the spigot ran piping hot water in which we dipped our hands. Hell, I might as well go for it, I thought. There’s no turning back now.

Less than an hour after it had breathed its last, we set about chewing on this poor goat. And chewing. And chewing. Never have I ever tried to chew through tougher meat. And boy, was there plenty of it! As I was working away at the first bite the cook came over and plopped a giant wad of green goo on the nyama choma plate. Ben identified it as fried mash of potato, maize, and kale. It was delicious. And with the other garnishes, so was the goat. I made the mistake of sampling one of the innocuous-looking peppers. It took a bottle of Tusker to cool a single bite. Even then, my fingers burned all day, and the less said about contact lenses the better.

Conversation ceased as we busied ourselves with stuffing our faces. Bosko finally joined us carrying a third plateful of nyama choma. By this time I was full to bursting. My two rail-thin companions agreed that they’d had plenty. I thanked them wholeheartedly and agreed that this meal would stand out as unique among all my dining experiences. We then picked our way back out to the car through the goats and the people and the smells and sounds of Kiamaiko.

I survived my four low-budget days in Nairobi. Most of the rest of my meals I bought from street vendors in Tsavo Road: hot, tasty, and about one-tenth of what the Hilton tourists were paying. And as my plane took off for Madagascar I was still picking nyama choma from between my teeth.

© 1995 Danny Carnahan